Jobs & the Economy

As pint-sized AVs beat a path to your front door, how can cities harness them to strengthen local economies?

The dog never saw it coming. Last April, a delivery robot the size of a washing machine trundled down the sidewalk in San Francisco’s Mission District, dodging buskers and hawkers before nearly running over a dog. The robot, named Marble, stopped in the nick of time.

But why was it on the sidewalk in the first place? Aren't we all supposed to be getting our burritos delivered by drone already?

Yelp and Eat24 conducted a food delivery pilot bringing Marble’s robots to San Francisco in 2017. (Image: Marble)

Urban airspace is still off-limits for restaurants as aviation authorities scamper to write new rules for robot flyers. So for instant delivery startups the value of sidewalks is obvious—it’s a lot easier to invent an autonomous vehicle that can navigate the relative safety of pedestrian zones than one that can survive among cars and trucks on the street. That’s what London-based Starship Technologies is betting, having successfully lobbied several states to approve its delivery droids. They’re already at large in Washington D.C., delivering pizza and sundry items on behalf of Postmates as part of a pilot approved by the district.

Retail’s Robot-Powered Restructuring

Challenge. Cities need jobs and small businesses that can withstand the coming onslaught of automation.

It’s too early to say whether cities will widely regulate these sidewalk juggernauts, though San Francisco has already adopted tight restrictions in anticipation of future conflicts. But the arrival of hyperlocal deliverybots of all shapes and sizes—let’s call them conveyors—raises a more urgent economic issue. Can local merchants survive in an age of instant robot delivery?

The D.C. trial highlights how today’s conveyor prototypes are being pitched as a boon to local restaurants and shops. Their low speeds and limited range are an ideal match for last-mile deliveries that are made by car or (electric) bicycle today.

But it’s not hard to see how conveyors could help online mega-stores like Amazon, Jet, and Alibaba build a new distribution system to bypass main street merchants.

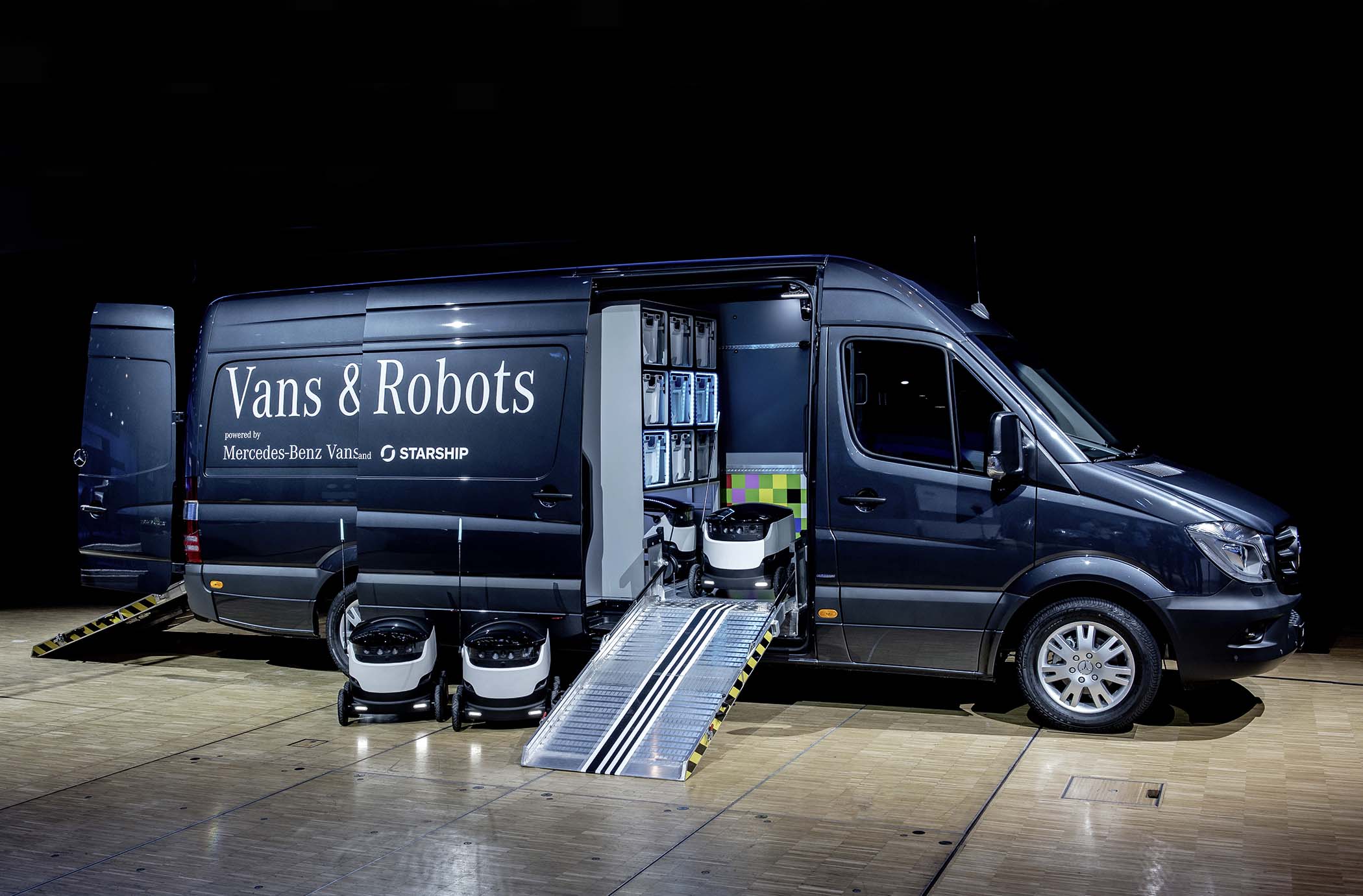

This was what Mercedes-Benz had in mind last year in Starship's hometown of Tallinn, Estonia when it unveiled a Sprinter van retrofitted as a mothership for up to eight Starship conveyors (and subsequently announced a $17.2 million investment in the startup). Topped off with popular items at the same-day delivery hubs being built at the edges of big cities today, these roving depots could target areas as small as a few blocks for truly instantaneous deliveries of everything from consumer goods to pre-cooked meals, beating local businesses to customers' front door.

Industry visions for AV deliveries undervalue human workers and the public realm. (Image: Mercedes Benz)

The vitality of local main streets and the jobs they create could be on the line. With e-commerce sales in large metro areas expected to grow 85% by 2020, and with Amazon's aggressive push into brick-and-mortar retailing, it's easy to envision a future in which AV conveyors cater to customers' every whim while decimating local merchants and employers.

The challenge for Main Street merchants is figuring out how to harness conveyor technology as well as the big guys. It's counterintuitive, but a robust local conveyor system could actually eliminate the biggest competitive advantage of mega-retailers like Amazon—their same-day delivery services.

Machine Learning, Meet Common Sense

Solution. Shift the human role in logistics from driver to curbside porter, working in collaboration with delivery AVs.

Leveling the playing field for conveyor commerce means cities will need to take a more active role. One place where interventions will be needed is on the receiving end of automated deliveries. There are two problems.

The first has to do with time. All of the AV delivery trials to date depend on customers meeting the conveyor at the sidewalk or curb to fetch their package or meal. But as Arizona State University assistant professor David King notes, this is the weakest link in the autonomous delivery chain. “They’re not waiting for a package to arrive. They’re going to be on the phone, or in a coffee shop. People are never ready on time. For these systems to work, the recipient has to be ready.” They also have to actually be home, which isn’t the case for a majority of parcel shippers such as UPS and FedEx.

The second has to do with terrain. Look at all the trouble driverless cars have had city streets. Numerous challenges await as they try to navigate elevators, stairs, and locked front doors, many of which are outside the range of GPS and cellular signals. It will be a long time before conveyors can actually get to your door consistently and safely.

A student at Tallinn University of Technology receives one of the first-ever food deliveries by a robot in Tallinn in autumn 2016. (Image: Wolt)

Both problems create an opportunity for cities to demand conveyor schemes that are more effective, friendlier to pedestrians, and strengthen the local economy—by bringing humans back into the picture.

"The solution," as King suggests, "is to have someone who's always ready."

It’s an approach to handling deliveries that’s as old as cities themselves—porters. Porters could solve conveyor companies’ hardest technical problems, such as entering buildings and traversing elevators and stairs. They could also smooth the traffic jam on sidewalks and at curbs, soothing cities’ anxieties about the robot invasion.

Locally-Grown Automation

But where porters could tilt the scale for local economic development is by transforming the existential threat of an Amazon- or Walmart-controlled AV distribution system into an avenue for small business growth.

Porters could also boost local economic development by playing an important role in fostering consumption of locally-produced goods and services. Having a human touch at the last meter introduces opportunities for porters to coordinate services that compliment deliveries, like assembly or tech support. Cities could empower business improvement districts and local merchants’ associations to mobilize porter services. And as trusted middlemen with street cred to bridge the divide between neighbors, porters might unlock opportunities for micro-businesses and sharing economy ventures.

The employment generated by a porter-powered conveyor network could be a welcome counterweight to an ominous trend. Oxford economist Carl Benedikt Frey predicts 80% of the jobs in transportation, warehousing, and logistics are vulnerable, which is an especially frightening prospect in 29 states where this sector represents the single largest source of employment, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

As familiar neighborhood icons, porters would be in an ideal position to provide add-on services after deliveries, helping people install and assemble products, recycle packaging, and other pesky household tasks that are not easily automatable.

Slideshow:

Automation Empowers Local Economies

A growing array of delivery AVs will bring unprecedented convenience, but at what cost? Meet Sally, who finds a neighborhood porter can fill an essential gap in the logistics system.

Illustrations: Studio Muti

Swipe to advance the slideshow →

Who Will Pay the Porter?

City Strategies. Cities need to shape automated delivery systems to balance the priorities of local businesses, residents, and online retailers.

The biggest question around porters is who will employ them. After all, the economic tailwind driving the rise of conveyors is shipping costs. Starship has claimed it can cut the cost of fulfilling an instant delivery in central London from its current £12 ($16) to under £1. Much of that savings comes from cutting human workers out of the picture.

But in cities, where delivery densities are high and there are strong incentives to maintain an efficient and orderly conveyor network, there are lots of possibilities for financing a human touch at the last meter of delivery. King imagines homeowners associations or residential buildings happily footing the bill to keep sidewalks clear, essentially lengthening the job description of doormen. Cooperatives could mobilize the unemployed as on-demand gig workers. Chambers of commerce and other small business associations could pool resources, perhaps in marketing agreements with conveyor operators. Municipalities might operate their own conveyor networks, or strike partnerships with delivery companies or e-commerce giants in lieu of restrictive regulation. Postal systems might even finally see the potential to reinvent their own offerings.

Interested in learning more about how this could take shape in your city? Download our Innovation Brief, which provides detailed information on the challenge, solution, use cases, and implementation strategies.