Urban Transformation

As automation speeds up and spreads out over the next decade, can it be harnessed to create better neighborhoods?

During a mobility conference held at Google’s Silicon Valley headquarters several years ago, the company’s “captain of moonshots,” Astro Teller—who at the time oversaw its autonomous vehicles program—ruminated on the mid- to long-term future of AVs. “We’re finally getting to a place where reconfigurable buildings are happening,” he told astonished attendees. “What that’s going to look like, I don’t know. We might need self-driving buildings as well as self-driving cars.”

What if cities could combine the best of muscle power, motor power, and machine intelligence? (Image: TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP/Getty Images)

Although easily dismissed at the time as an example of tech industry hubris, Teller’s musings feel increasingly prescient. Autonomous upgrades to familiar forms of urban transportation are already arriving—taxis, minibuses, and delivery vans. But still other, genuinely radical possibilities for urban AVs are appearing on the horizon. If these ideas become inventions, they could reshape cities as much as electricity or the automobile did in earlier eras.

Imagine a future with self-driving scooters, smart electric-powered bikes, and even skateboards that zip us to transit stations beyond the reach of foot or pedal power alone; buses under precise computer control that feel like they’re riding on rails and link up into virtual high-capacity trains; or, in place of the ineffective jumble of signs, meters, and signals that try to bring order to today’s chaotic streets, benign robocops that serve us, not automobiles.

Could autonomous vehicles help cities expand access to affordable housing, unclog public transit, and take back the streets from private cars? These improvements in city life are still down the road. But they could come sooner than we expect. Just like the sudden breakthroughs in self-driving cars, these more radical ideas about urban automation could accelerate from zero to 60 in no time. This begs the question: how can cities harness these innovations before industry steers a different course?

Where the Robot Meets the Road

Challenge. People need streets that are safe, pleasant, free-flowing, and fairly shared.

Solution. Replace low-effectiveness street fixtures with intelligent AVs and municipal robots.

City Strategies. Cities need to establish a long-range vision for streets and public space, including desired uses, management, and governance, and fiscal constraints to define how this solution could be designed and implemented.

One city that’s serious about finding the answer is Paris.

By the time the world turns its attention to the “City of Light” for the 2024 Summer Olympic Games, the Champs-Élysées will be empty of cars. Or conventional ones, anyway. The city has started by banning diesel engines by 2020, joining London and Helsinki in their commitment to squeeze automobiles from their city centers. Replacing them will be electric vehicles of all shapes and sizes, from cars to scooters, bicycles, and buses.

Meanwhile, Paris is increasing the price of parking, adding bike lanes, and investing in street furniture. What happens when not just the vehicles, but also previously stationary objects in the streetscape, gain at least a measure of autonomy?

Will today’s internet-connected info kiosk become tomorrow’s self-driving neighborhood concierge? In London, British Telecom’s InLinkUK devices are replacing the iconic red telephone booths that once filled London’s walkways. (Image: InLinkUK)

“The robotization of the city” is just beginning, says Paris deputy mayor Jean-Louis Missika, whose purview includes architecture, urbanism, and economic development. In the future, autonomy won’t be limited only to vehicles designed to carry humans or cargo. While Google’s self-driving buildings still seem like a stretch, it’s perhaps not as difficult to imagine an autonomous parking meter or traffic light. What if all of these functions were enfolded into the same device?

These contraptions (let’s call them “urban ushers”) could seamlessly fill a multiplicity of roles—robotic traffic cop, crossing guard, and meter maid all in one, with capabilities that go far beyond what’s currently possible. Directing AV traffic and translating instructions into signage for pedestrians requires multiple technologies that haven’t been invented yet. These include a variety of vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure communication protocols needed to fulfill many different duties.

With an interest in social impact and public safety, Hitachi is exploring the benefits of having robots act as urban ushers. (Image: Hitachi)

A preview of how ushers might function is provided courtesy of Hitachi’s experimental “patrol robot,” a trash can-sized concept AV recently featured in a company promotional video. With a penguin-shaped chassis, and small flipper-like arms it waves to get attention, the adorable droid enhances safety in the public realm by greeting school children and seniors by name, summoning paramedics during emergencies, and providing auxiliary street lighting—all 24/7, over and over, without overtime pay. Future ushers might also allocate curb access in real time using dynamic pricing.

While the idea of municipal robots is sure to raise fears of civil servant layoffs, smarter streets could replace revenues lost when AVs reduce parking fines and traffic violations. Cities could divert staff freed up by ushers to policing, schools, and community services.

It seems a stretch to imagine ushers will be ready in time for the 2024 Summer Olympic Games, but Missika is intrigued all the same. “Because Paris is so dense, we have so few street spaces, and so we need to use them optimally,” he says. “Even a bench can be mobile”—redeployed at will around the city to bolster university seating during exams, for instance. “The idea that you can organize the answers to these needs with street furniture or services that are temporarily mobile is very interesting.”

Slideshow:

Automation Creates Responsive Streets

Advances in AV and robotics technology will allow everyday street infrastructure to become intelligent and mobile. Cities can put this to work by making streets more adaptable to a changing array of public and private uses.

Illustrations: Kristin Boydstun

Swipe to advance the slideshow →

All Aboard the SoftTrain

Challenge. Cities need ways to quickly deploy high-quality, high-capacity transit with minimal capital.

Solution. Automate bus rapid transit (BRT) systems to enable multi-vehicle platoons.

City Strategies. By defining use cases and deployment scenarios, cities can engage industry partners needed to implement this solution.

Urban ushers show what might be possible when cities take a clean-slate approach to autonomous vehicles, sweeping away old infrastructure to make way for a new solution. But what about using AV technology to improve on existing solutions?

With its combination of pre-paid boarding and dedicated lanes, bus rapid transit (BRT) has been the most powerful new urban transport innovation in the last 25 years. By deploying high-capacity mass transit at a fraction of the cost of digging subway tunnels, planners in many cities have succeeded in increasing urban density in walkable zones around BRT stations.

But despite its remarkable success, BRT is bumping up against a number of limitations. The most important of these is capacity. With a maximum throughput of about 40,000 passengers an hour on the most highly geared lines, BRT isn’t a drop-in replacement for rail, which maxes out at nearly double that volume.

According to Transit App Moovit, one in every 5 passengers on Bogota’s public transit system transfers twice on a single journey. This picture in 2017 captures passengers as they wait to board one of Bogota’s TransMilenio’s BRT service. (Image: Flickr)

This is where autonomy could come in. Today, both Silicon Valley startups and old school automakers are road-testing AV trucks that link up in tightly spaced convoys, cutting fuel and labor costs. Applied to buses, the same technology could remove existing limits on vehicle length, boosting capacity well beyond today’s limits.

The longest buses today are the bi-articulated models used in Curitiba, the Brazilian city that sparked the BRT craze. These giants use flexible joints to link three coaches carrying a total of more than 250 passengers. But AV bus convoys (or SoftTrains as they’d inevitably be rebranded) might use AV technology to couple six or more vehicles, theoretically doubling what’s possible today. Virtual linkages would also fix articulated buses’ Achilles heel—their inability to navigate turns on tight city streets. Coaches in a SoftTrain would simply spread out momentarily to curve around a bend.

SoftTrains could also make BRT more versatile and flexible than it is today. Driverless buses could be far more rapidly deployed for emergency transit services during crises or disaster recovery, with less unexpected cost. SoftTrains could be a tool for quickly testing the feasibility of potential BRT routes, just as BRT is often used to pioneer development along future rail corridors today.

The ability to link up and split apart at will would allow “dual mode” operation SoftTrains that serve multiple branches off main corridors, a feat impossible with today’s vehicles.

Finally, computer control also promises a bevy of smaller improvements to today’s BRT, including smoother speed changes, faster docking, and more precise steering. The result would be a more comfortable ride, shorter stops, and narrower lanes than are currently needed.

Slideshow:

Automation Augments Buses

Computer control will allow buses to link up in multi-coach trains that carry more people. Cities can leverage automation to expand the capacity and improve flexibility of bus rapid transit.

Illustrations: Studio Muti

Swipe to advance the slideshow →

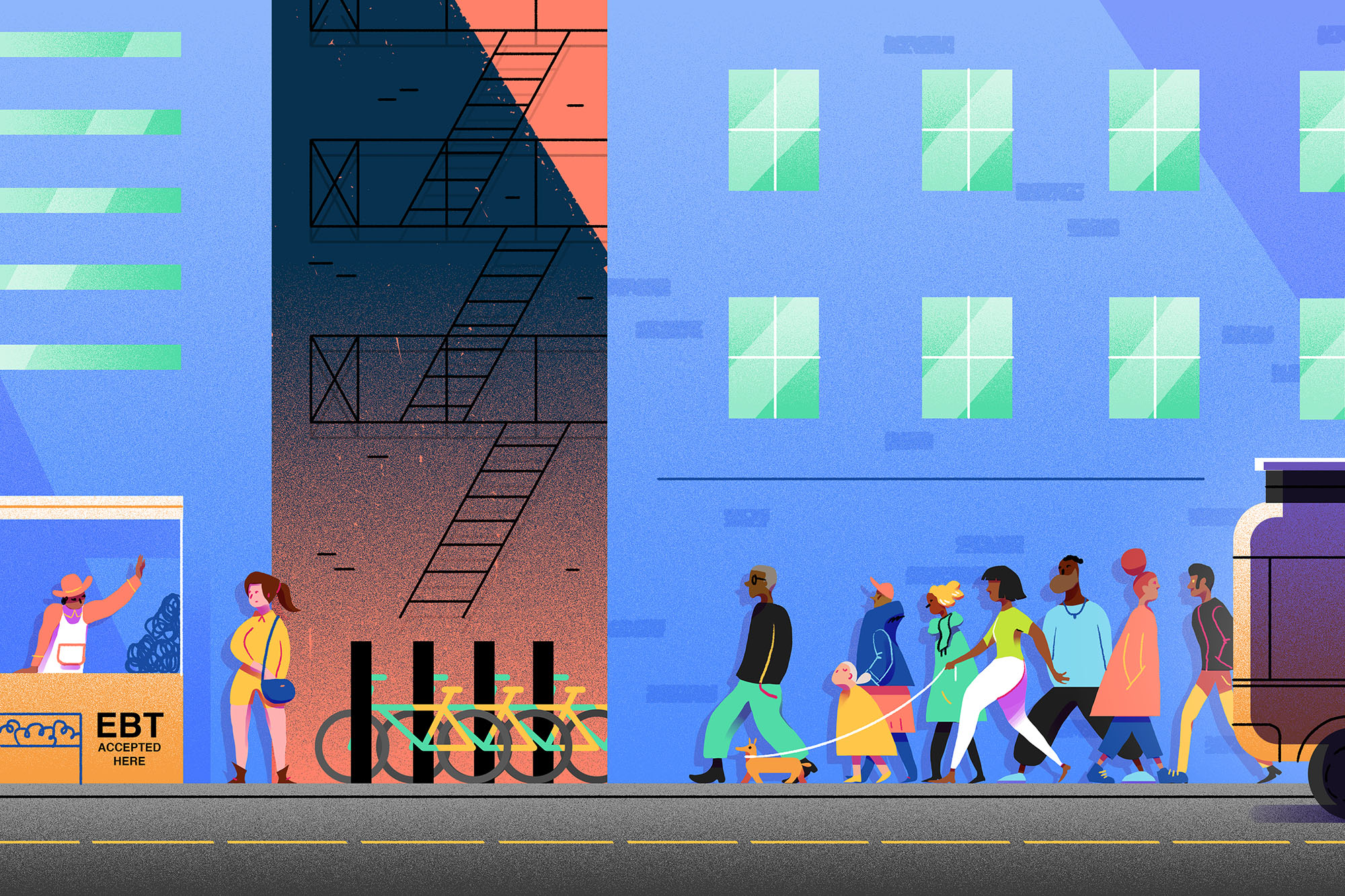

Last-Mile Rovers

Challenge. People need transportation and housing options that don’t force them to choose between affordability and livability.

Solution. Encourage small automated personal vehicles that stretch the last mile to five miles.

City Strategies. Cities will play a modest role in kick-starting rover systems, but stand to make substantial gains if they exploit possibilities for the larger land use and transportation reforms unlocked by this scenario.

Urban transit agencies are masters at strategy, employing buses and trains to efficiently move masses across metropolitan areas. It’s the tactical battles—the short hops that planners call the “first-mile/last-mile”—where challenges remain.

That’s why the big mobility innovations of the last decade are all small-scale. The rise of urban cycling, bike share, and now dockless bike share stem from rising demand for door-to-door mobility. Now, a swarm of startups are jumping in, making electric bikes, scooters, and hoverboards—personal electric vehicles (EVs). Retailing for under $1,000, these vehicles (we call them “rovers”) typically cover a range of 20–30 miles, at speeds of up to 15 mph.

Jump’s GPS-enabled dockless e-bikes, now part of the Uber mobility network, are available in 3 cities with additional plans to launch in Providence, RI by the end of the year. (Image: Jump Bikes)

Unsurprisingly, the group most eager to zip about on these electric carpets are people under 35. But it isn’t just the speed boost they find thrilling—these contraptions are the best new way to escape from skyrocketing rents.

In the home price run-up of the U.S. sub-prime lending bubble in the 2000s, first-time buyers were often advised to “drive until you qualify.” The flight to new development on lower-cost land at the metropolitan fringe fueled intense urban sprawl. Today, an influx of young people into more central urban areas is driving up prices there instead. The ensuing price pressure has pushed many into still-affordable neighborhoods just beyond the limits of transit networks.

New transportation options are the glue that’s helping bring these once-peripheral urban districts back into the urban pulse. Rovers are playing a rapidly growing role by dramatically expanding people’s comfortable range of travel. The rule of thumb for planners is that people will walk no more than 20 minutes to a transit stop, which translates to about a mile. On a rover, the same person can cover five miles in that amount of time. Lower rent is suddenly within reach.

Could cities embrace this hack, put their weight behind this new mode of neighborhood travel, and supersize transit-oriented neighborhoods?

One obvious approach—that will mean waiting for automotive self-driving technology to be scaled down to personal vehicles—is rethinking bike share as an all-AV affair. A citywide fleet of self-driving rovers would come when called (by app of course, or even predictively based on past travel patterns), dock in out-of-the-way locations like alleys and garages, and never be caught out of place.

“You won’t need to think about balancing or steering [the system], says Derrick Ko, CEO of the stationless bike-sharing startup Spin and a former manager at Lyft. For Washington D.C.'s Capital Bikeshare system, rebalancing accounts for more than half of the system’s operating costs. With rovers, the system rebalances itself.

Rovers’ addressable market could also put bike share to shame. One feature they will all share is electric motors, enabling young and old alike to ride in comfort if they can’t or don’t want to pedal themselves. And while no one has invented a two-wheeled self-driving bicycle yet (though MIT has a three-wheeler), the panoply of different personal AV/EV combination vehicles already available—from scooters to wheelchairs and beyond—shows that a rover system could provide sustainable, human-scale mobility to a much wider range of people than today’s bike share.

Slideshow:

Automation Improves Access to Housing

Small, personal vehicles will combine electrification and automation to greatly extend individual's’ range of movement. Cities can exploit this mobility enhancement to connect outlying areas to transit.

Illustrations: Nick Iluzada

Swipe to advance the slideshow →

Interested in learning more about how these ideas could take shape in your city? Download our Innovation Brief, which provides detailed information on the challenge, solution, use cases, and implementation strategies.