Sustainability

Private shuttles carry a fast-growing share of commuters. But can driverless technology give the company bus a vital role in public transit too?

Challenge. As automation drives sprawling growth of driverless shuttles, cities need ways to reduce redundancy and expand public access to private transit systems.

Soon, Apple’s employees will have a new way to commute to their gleaming glass donut: driverless shuttles endlessly weaving their way through Silicon Valley. They’ll join dozens of cities across the globe that are already evaluating this new technology. Compared to Tesla’s autopiloted sedans or Waymo’s self-driving minivans, these boxy minibuses are painfully slow and unsexy. But with 12-passenger capacity, they’re practical people-movers, and since they run only on pre-programmed routes they’re much simpler to design. That’s why they’ll probably be the first AVs that millions of people experience—whether at work, school, sporting events, or a shopping center.

For nearly two years, two driverless shuttles have operated between the city center and train stations in the Swiss town of Sion. (Image: PostBus)

Automated taxis are still a risky proposition, but a pair of French startups—rivals Navya and Easymile—have already shuttled 1.5 million passengers aboard its minibuses. Driverless shuttles are simple to deploy and easy to operate; how long will it be before they’re roaming campuses all over the world?

An Old Idea, Unleashed by Automation

In the world of urban transport, private shuttles are hardly new. Navya and Easymile are merely installing autonomy in the vans and buses operated by employers, schools, residential buildings, and even malls, which invisibly trace their way through cities every day. These services are typically exclusive and therefore inefficient, filled with empty seats on overlapping routes occasionally competing with, rather than complementing, transit.

No one paid much attention to the metastasizing growth of private shuttles until Google’s convoys reached a flash point in San Francisco. But what happens when plug-and-play AV driverless shuttle fleets make it easy for thousands of startups to roll their own door-to-door services? (Navya claims its AVs cost 30-40% less to operate than conventional transit.) Will the streets of London or Austin be jammed with half-empty buses?

Can Cities Connect the Dots?

Solution. Catalyze the creation of a data integration layer and rider credential scheme to encourage interconnection and public access to privately operated shuttles.

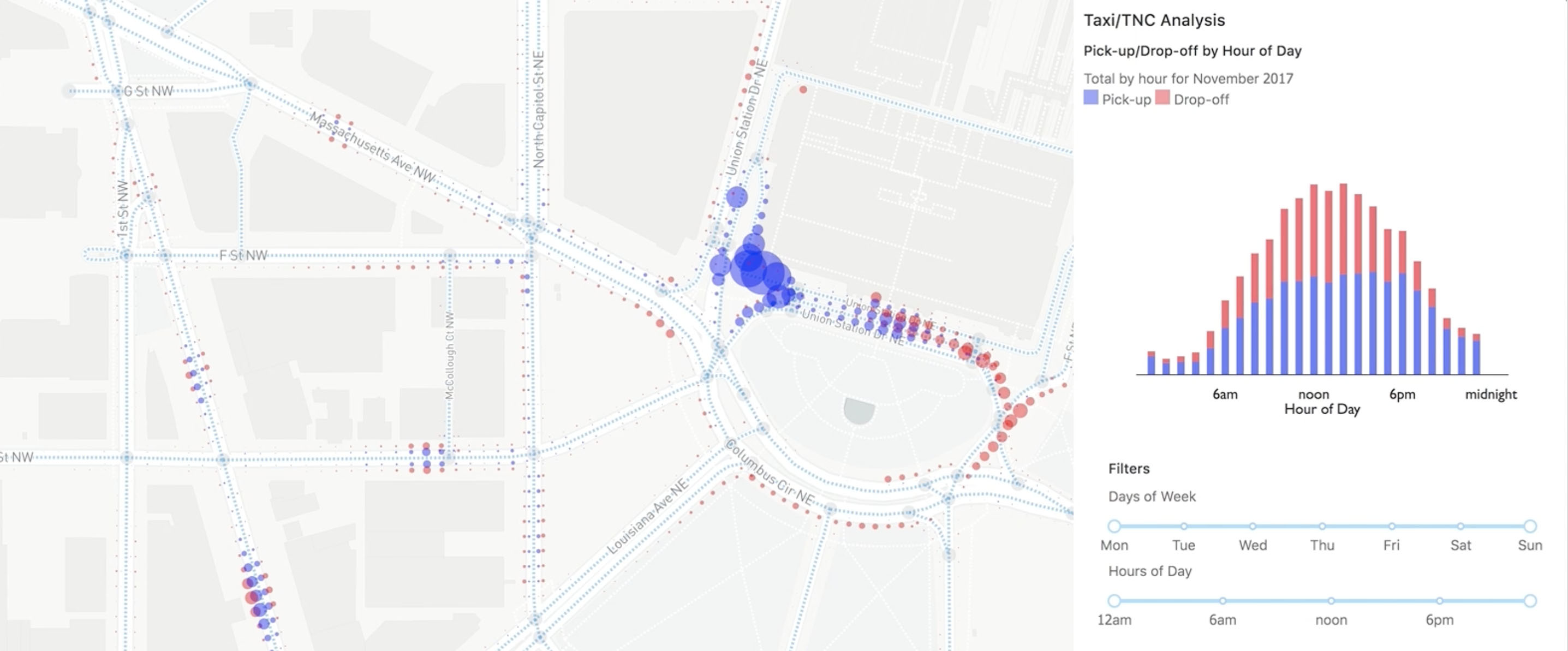

Many cities already regulate shuttle operations, limiting routes and stops, as well as a new category of private fixed-route services mobility experts have dubbed ‘microtransit’. But automated and connected shuttle operations may present a unique opportunity to step in and knit these overlapping networks together, creating a kind of microtransit mesh. Cities could offer incentives to operators such as grants, carbon offsets, and tax or regulatory relief in exchange for citywide data sharing on service level and vehicle locations, which at the very least would offer a bird’s-eye view of the entire system. From there, city leaders could work with operators to create rider credentials, cross-honoring agreements, and connection points to expand the access and reach of each network.

Over time, an open, interconnected system of driverless shuttles could emerge as part of a larger mobility-as-a-service platform, combining public and private modes alike. People could simply hop aboard whichever vehicle was going their way, regardless of who owned it.

Slideshow:

Automation Enables Shared Shuttles

Driverless minibuses will make it easier for more organizations to run private shuttle systems. Cities can push for technologies to link these services up and extend public access, creating an efficient alternative to driving.

Illustrations: Kristen Boydstun

Swipe to advance the slideshow →

The Challenge of Cooperation

City Strategies. Use regulatory authority and a range of incentives to make participation in this solution a feasible and appealing path for operators.

All of this assumes several critical pieces that haven’t yet been built. The first is the kind of comprehensive data sharing that ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft have been loath to provide, citing trade secrets. Now that data is the new oil, hoarding it makes sense. An instructive precedent is the travel industry model pioneered nearly 60 years ago by Sabre—the first and still largest global distribution system for booking flights, hotels, and car rentals.

Sabre and its subsequent competitors linked ticketing systems run by each airline, offering a holistic view of seat availability and prices across the industry. This data was shared first with travel agents, and then later with a slew of web-based services in the 1990s. The democratization of air travel would have been impossible without online bookings. But Sabre’s legacy systems depend on standard industry-wide product definitions. Over the years this top-down approach to coordination has limited newer airlines’ ability to create innovative new services that don’t fit within old data schemes.

Eager to both accelerate the data sharing process and avoid the same data governance mistakes when it comes to urban mobility, researchers at the University of California at Berkeley’s Transportation Sustainability Research Center have proposed creating third-party repositories where companies and cities could deposit anonymized data in a more bottom-up cooperative model. In October, the National Association of City Transportation Officials and the Open Transport Partnership launched the SharedStreets data platform, with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Their goal—creating the standards for coding city streets and a one-stop-shop for the coming wave of AV-generated data.

SharedStreets provides a non-proprietary data standard and open platform that allows cities to exchange street-level data with other public and private sector organizations. (SharedStreets)

But this is only the first step. “We’re having conversations with mayors” who are “saying ‘what steps can you take to make a marketplace emerge?’” says Kevin Webb, co-founder of the Open Transport Partnership. “That’s bigger than building a single service.” On top of the raw data an urban marketplace for microtransit rides would need to define the criteria used to evaluate different options. Over time, just as Travelocity and Expedia rely on Sabre’s data standards to price and select airline seats, hotel rooms and suites, and rental cars of all makes and sizes—third-party apps could use open data sharing to book passage on driverless shuttles across an entire city.

But what will it take to compel or incentivize operators to open their networks to outsiders?

“Data sharing would be the minimum for any permit we would grant” to a driverless shuttle operator, says Seleta Reynolds, general manager of the Los Angeles Department of Transportation.

Shadow transportation networks pose a threat to public transit in that they run the risk of cannibalizing ridership, Reynolds notes. But they also pose an opportunity to bridge service gaps and reallocate public transit resources away from areas where private services already fulfill local needs.

A Ticket to Ride

Digital technology could also play a decisive role in opening up a bigger private shuttle fleet to the broader riding public. There are already many gradations of open access to shuttles within any given city. Reynolds points to the San Francisco Bay Area, comparing Google’s employee buses and the Emery Go-Round—a free shuttle service open to the public, subsidized by business owners in Emeryville, California. How can cities incentivize more private shuttle operators to share these services with nearby communities that could benefit?

The likeliest solution is the one taken by a slew of shuttle startups, including Ford’s Chariot, which uses an app to power both a public microtransit service and dozens of private shuttle routes in San Francisco, Austin, New York, and Seattle. It’s not difficult to imagine Chariot offering up its own rider verification tools as the base layer for a trusted ridership program on participating shuttles. (In other words, if Chariot says you’re good people, they might just let you aboard.)

Chariot is a microtransit provider that already uses its own digital rider verification tools. Could it become the basis for a broader trusted rider program in a microtransit mesh? (Image: Ford Motor Company)

Ultimately, there are other carrots and sticks at cities’ disposal to shape microtransit. Reynolds wonders whether public use should be a condition of curbside access, or would driverless shuttles welcome paying riders to help defray the costs? Better yet, she says, public agencies should consider investing in private AV networks. “Transit agencies would get credit for providing service,” she says, “but also have some say in how these systems operate and who benefits.”

Interested in learning more about how this could take shape in your city? Download our Innovation Brief, which provides detailed information on the challenge, solution, use cases, and implementation strategies.